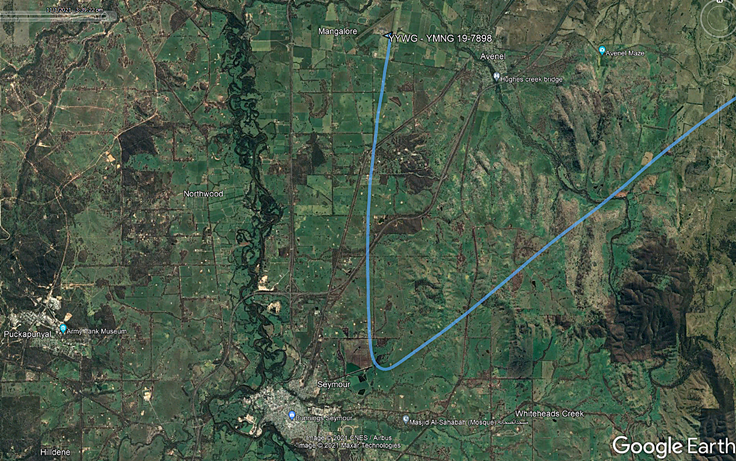

On November 1st, I took my grandson, Dorian, for a promised ride in the Sonex. We decided on a trip to Yarrawonga and return. Yarrawonga is on the Victoria/NSW border and the trip is about an hour each way. The trip there was uneventful, but on the return trip, we were approaching the town of Seymour, our last way point and only about 20 minutes from home when the engine suddenly ran very rough. I turned back for Mangalore airfield, about 7.5 nautical miles to the north. As we were turning the level of vibration became severe so I closed the throttle and the engine stopped completely. We were at 6000 feet AGL and almost lined up with runway 36 so it looked like we could make a safe landing, but the engine sounded terminal. I made a mayday call on the area frequency and had time to explain our situation to several others in the area who kept clear of the runway for me. From engine failure to touchdown took a little over 5 minutes. I initially thought we were going to be high and would have to wash off height but as it turned out we only just made the runway. We rolled to the first taxiway and turned off where we rolled to a stop, amazingly only 50 metres from a friend’s hangar.

Some years ago, a friend in the US had an engine failure in his Waiex and managed a forced landing at a former naval air base. I recall thinking “That would never happen in Australia. Airfields are just too far apart. Your chance of having an engine failure within gliding distance of an airfield are almost zero.” Obviously while the chances are lower, they are not zero.

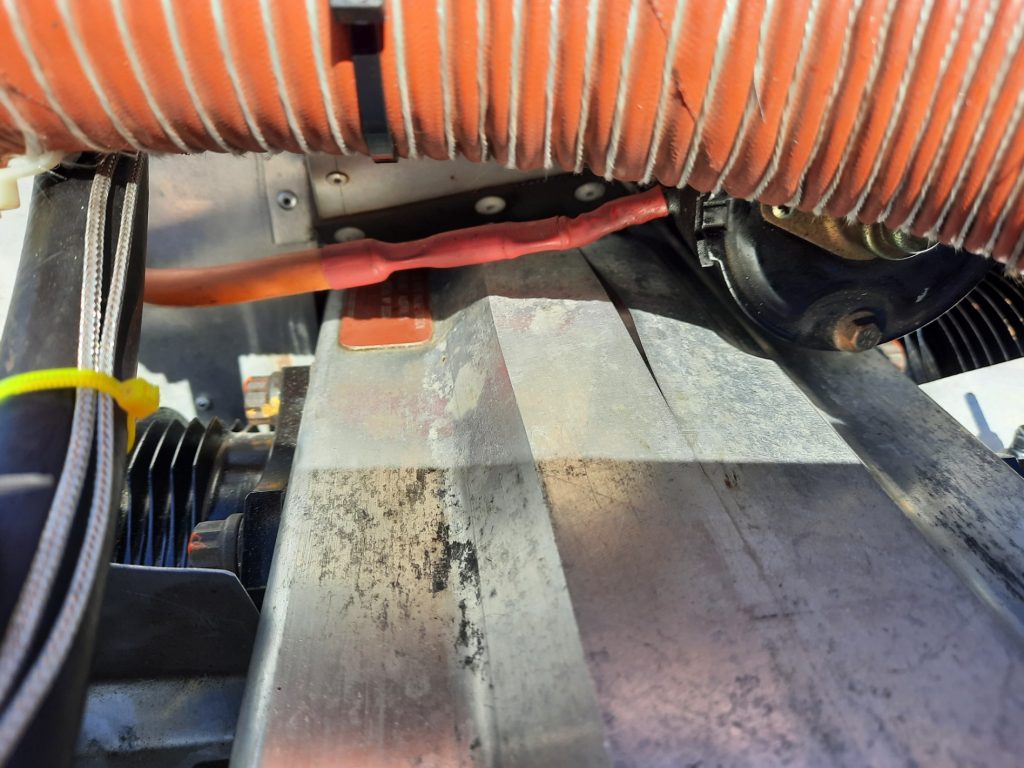

Here’s what greeted us when we pulled the cowling.

The engine problem was obviously major so I called Sue for a lift and Dorian called his parents to let them know our situation. About that time, Sonex flying friend, Brian Ham taxied in. We weren’t able to squeeze the extra Sonex into his hangar but he supplied tie-downs and even a canopy cover to safeguard things until I could organize a trailer. He even checked the tie-downs during some wild weather over the next couple of days.

Recovery

The following Saturday, Xenos builder, Brian Rebbechi joined me at Mangalore and the three of us made pretty short work of dismantling the Sonex and loading the parts on two trailers. The 20 minute flight to Kyneton became a 2+ hour drive.

The damage

The bump in the cases lined up with cylinder #5, so that’s where I started.

And the cause of all the trouble:

It appears that the exhaust valve has failed by fatigue, although the end of the valve stem is so hammered it’s not possible to be sure. With 20/20 hindsight I think it may have been possible to detect this crack when I had the engine apart 25 hours ago. I certainly cleaned and inspected all the valves before I reassembled them into the head but small cracks in hard materials like steel are very difficult to see. I do have a dye penetrant crack detection kit and that might have picked it up. Depends on the crack growth rate. It was likely very small at that time. A magnetic particle check might have picked it up. I had the crankshaft mag particle inspected but didn’t think to get the valves checked, but the whole reason for dismantling the engine was to check the crank. The rest of the inspection was incidental.

Engine details

Engine number 33A-116, built in 2000. Total time at failure: 477 hours. This was original heads and valves.

Regarding temperature monitoring:

EGT

From 0 to 190 hours the engine was fitted with the original “log” type exhaust manifold. With that type of exhaust it wasn’t possible to get some of the EGT thermocouples more than 75mm from the exhaust port so I was uncertain about how useful the EGT readings were. At 190 hours I machined the heads with a chamfer in the exhaust ports and fitted a late type 3 into 1 exhaust and fitted all the thermocouples 100 mm from the port. #5 has consistently been the highest EGT, usually up to about 720°C on climb and settling at about 670° to 680°C on cruise. The other EGTs have always been lower.

CHT

Until 450 hours, the CHTs were monitored by a thermocouple under one of the head bolts because there was nowhere else to fit them. Indicated temperatures were always low with temps evening out to about 120°C on cruise. #5 was always the hottest but rarely went above 150°C on the ground. At about 447 hours I had a loss of control on take-off in strong cross winds resulting in a prop strike. While the engine was stripped for checking I noticed that cylinder heads #1 and 2 looked like they had been running hot despite indicating low temperatures (both had tight exhaust valves from burnt oil residue in the guides and both needed the valve seats to be recut and valves synchroseated. I made a small change to the heads that enabled attachment of the thermocouples to a small fin between the two spark plugs. This resulted in about a 10°C increase in the indicated temperatures.

Ramblings

It appears that failures of exhaust valves like this are not entirely unknown to Jabiru. Here is a link to the report of a Titan Tornedo that had a similar failure in its Jabaru 2200 in 2015. https://www.accidents.app/summaries/accident/20151016X84916

I have also seen a detailed metallurgical NTSB report on this failure but I have not been able to find an online version.

Fairly recently (about 5 – 6 years ago) Jabiru changed their valve material, but the exhaust valves in my engine, and likely yours too, are bimetal valves, with heads made from a type of steel that is intended to withstand high temperatures, friction welded to the stem which is made of 214N stainless steel, also a type that retains strength at high temperatures. The NTSB metallurgical report appears to show multiple cracks but I have not been able to detect any other cracks in the broken valve stem. I have also not been able to find any cracks in other valves.

The NTSB report showed that the failures were in the stem material and the above linked report speculated that the 214N steel didn’t perform well at temperatures higher than 750C. Jabiru’s recommendation is a maximum EGT of 740°C in cruise. My engine never saw temperatures quite that high but with the vagaries of measuring EGTs and the fact that the exhaust is expanding rapidly, it could mean that the valve sees much higher temperatures. Certainly all the other EGTs were much lower. My feeling is that EGTs need to be kept well below 750°C, let’s say a maximum of 700°C (1292°F).